The Public Sector Climate Action Mandate requires public bodies to reduce their energy-related greenhouse gas emissions by 51% by 2030. This poses an unprecedented leadership challenge!

Having facilitated climate leadership workshops in several public and private sector board rooms, I have not encountered any objection to the target. There is consensus that climate change is real, that the implications are potentially catastrophic, that emissions need to be reduced and that adaptation measures are required in anticipation of inevitable climate impacts. But is knowledge enough to move leaders to action?

The Public Sector Climate Action Strategy put the leadership and governance challenge very well when it states that:

Leadership, underpinned by strong governance at all levels, is essential for the achievement of our 2030 emissions reduction and energy efficiency targets. Given that the total emissions from the public sector make up a small percentage of national emissions, the role of public sector should be viewed in terms of being catalytic to the overall transition to a decarbonised society.

The public sector can shape national decarbonisation policies and targets. In addition to eliminating its own emissions, the public sector can make a much more significant impact by taking on this leadership role. Public sector leadership will involve transforming its own operations and supply chain

s by promoting new workforce behaviours as systemic changes across whole organisations, including green considerations in public-sector procurement decisions, and embedding climate considerations in the budgeting process. There is an underlying “best practice” dimension to public sector leadership which can be leveraged across the whole of society.

I am not convinced that the reality of public sector leaders’ demands has been fully grasped. From my experience, most public sector leaders focus on what they see as achievable within their organisational boundaries to reduce emissions without disrupting business.

Leaders are reluctant to consider changes that might impact their funding model, require a review of their statutory remit, impact jobs, or require unfamiliar leadership skills for shaping joined-up endeavours in ambiguous, cross-boundary contexts.

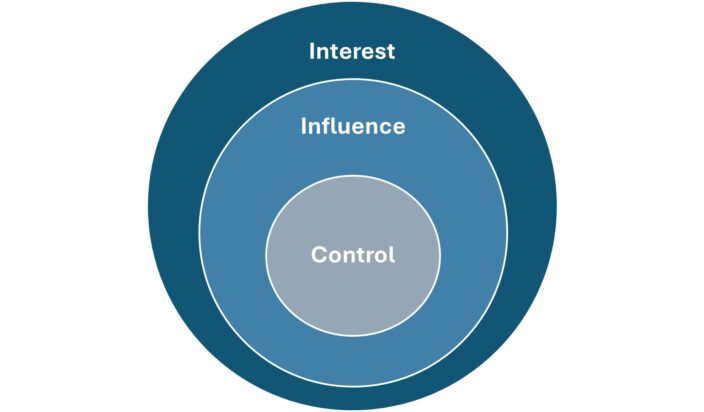

What zone are you leading in?

Leaders are comfortable leading in their zone of control, within the organisational boundary where the rules are clear, roles are understood and hierarchy is established and recognised. This is the zone that leaders have been trained to serve in. In this zone, leadership is about maintaining stability while implementing incremental improvements. However, a 51% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 demands a system-level disruption and a capacity to lead through instability.

The zone of influence lies outside the organisational boundary. It is occupied by other organisations you work with or for, organisations with whom you have an overlapping mission, government departments and communities affected by your activities. Leading in this zone requires leveraging interdependency with empathy and emotional intelligence.

Leading in the more ambiguous zone of influence requires a clear organisational identity. The ability to carry that sense of identity is vital, given the everyday churn in individuals occupying relevant roles across all organisations. My experience is that many public sector leaders are more reticent and less confident in this zone. However, I believe this zone is where public sector leaders can contribute the most to changing the system. A 51% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions requires system change.

The Climate Action Strategy calls on the public sector to lead a whole of society transition. This is the public sector’s zone of interest. The Strategy points towards what is asked by stating:

“climate action needs to be considered an integral activity that permeates the work of public bodies rather than as a separate add-on”.

This echoes Mahatma Gandhi’s observation that any of us can amplify our leadership impact by “being the change we wish to see in the world.” Understanding the science, discussing change, and publishing action plans is not enough.

Climate Leadership Skills

In climate leadership workshops, we invite delegates to consider the future leadership skills required of public sector leaders in the context of a climate and biodiversity emergency. It can be an uncomfortable conversation because the gap between leadership as practised and the leadership required is sometimes daunting. Typically, the future climate leadership skills identified by Board members include:

A strong sense of duty, purpose and service: a commitment to something much bigger than personal or organisational interest. This commitment cannot be faked.

Empathy, emotional intelligence, humility and humanity: extending space and time horizons and developing the capacity to feel the pain inflicted on others through climate and biodiversity disruption even when those others are distant from them.

More courage: without the courage to practice them, all other climate leadership skills are redundant. To catalyse a societal transformation, climate and biodiversity action must be sufficiently aggressive to cause nervousness. Without nervousness, it is almost certain that ambition is absent.

Inspire and demonstrate moral leadership: this is about inspiring and uniting others around a common purpose without seeking credit.

Cultivating transformative partnerships: moving beyond traditional organisational strategies, tactics, incremental improvements and putting society and the planet first.

Where to start

Of course, this is easier said than done. For many, it can seem like a lot of sacrifice. However, I believe that public sector leaders who build the capacity to navigate successfully at this level will build enormous reputational advantage and a positive legacy.

When thinking of the most fundamental climate leadership skill, I believe it is less about implementing action plans to achieve pre-determined organisational outcomes and more about facilitating relational processes, convening meetings, and holding challenging conversations with purpose, kindness, and tenacity.

Margaret Meade, anthropologist and author, put it well:

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful committed individuals can change the world. In fact, it’s the only thing that ever has.”

This article was published in the June 2024 edition of the PAI Review

Share this on...