[Context: Reflections on today’s news story of government acknowledgement that Ireland’s 2030 climate targets will not be met and emerging research on governance transformation.]

The stance is one of disciplined doubt. Being curious about what we know, don’t know and what we don’t know that we don’t know. There is a space outside the frame, beyond the edge of reason. Sometimes we can sense the energy in that space influencing what’s in the field, mingling with us. It might transmit a presence that is felt as a sense of unease, the discomfort of not knowing, or indeed a sense of possibility or the anticipation of a promise to be revealed.

When the energy from outside the frame enters the field, it may take material form as an “impossible object”. An impossible object is something that exceeds the descriptive capability of our available grammar. It holds an excess of meaning, more than we can metabolise. The impossible object reminds us of something we have forgotten, overlooked or refused to see. It might be the announcement of a debt that we owe but have never acknowledged. It is almost always the learning that precedes the learner. Climate change is probably the quintessential impossible object of this time.

When an impossible object is too big to metabolise, the field is effectively stuck with it. The object just sits there. As human participants in the field, we may comment on the object, argue whether it is real or not, debate who or what caused it to appear, offer proposals on what should be done about it and who should do it, but because the object is too big, because it holds so much information in excess of what our grammar can accommodate, our utterances and initiatives have little impact.

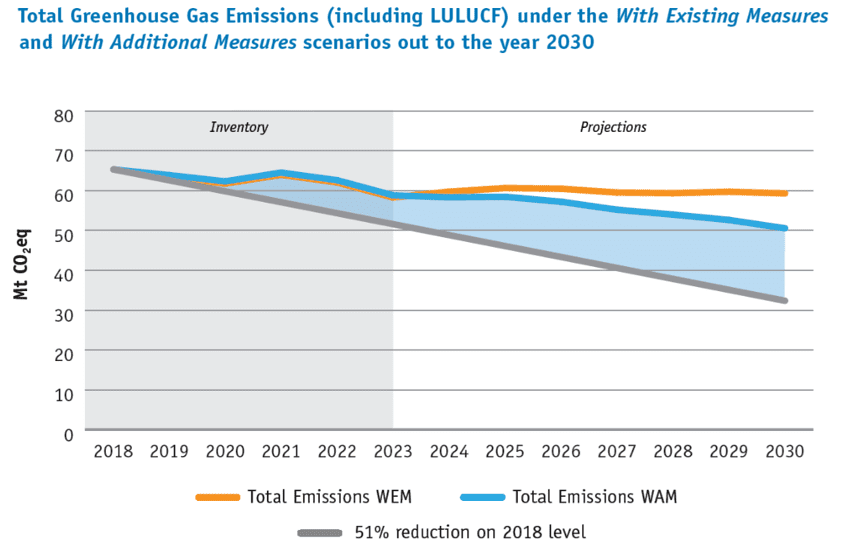

As the frailty of our efforts becomes evident, there is a temptation to give up and move on, just pay the €28bn fine if it comes to it. Other objects, say trade, geopolitics, migration, or AI, seem less impossible (or perhaps the extent of their impossibility remains unrecognised). Inevitably, obviated objects become obvious. The challenge is to stay with what we know we don’t know, and to resist reducing the field to what we are capable of knowing.

This doesn’t mean doing nothing. No, it’s a different type of work that calls for the development of governance that is less about optimising what is easy to know and more about discovering and giving form to new grammars that recognise objects based on what they are not, more than on what they are. It requires an apophatic stance, which requires remaining with the impossible object and not walking away.

Maintaining the stance requires a disciplined practice of capability development. We can begin by working in new ways with micro-impossible objects, tracing the contours of what’s possible, impossible, sayable, unsayable, gateways, lock-ins, the constraints and opportunities revealed in doing so and how they move through each iteration of a learning cycle.

The micro-impossibles often show up as micro-stresses or micro-opportunities. These could be community energy projects that challenge investor-driven models, catchment management that requires inter-agency coordination, or citizens’ assemblies that surface perspectives that governance has no mechanisms to integrate.

We need to get good at the micro if we ever have a chance of being competent at the macro. I’m exploring how working with micro-impossibles might develop new governance capabilities. And I’m curious what others are seeing in their own contexts.

Share this on...